Robust gradient-based MCMC with the Barker proposal

Source:vignettes/barker-proposal.Rmd

barker-proposal.RmdThe rmcmc package provides a general-purpose

implementation of the Barker proposal (Barker 1965), a gradient-based

Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm inspired by the Barker

accept-reject rule, proposed by Livingstone and

Zanella (2022). This

vignette demonstrates how to use the package to sample Markov chains

from a target distribution of interest, and illustrates the robustness

to tuning that is a key advantage of the Barker proposal compared to

alternatives such as the Metropolis adjusted Langevin algorithm

(MALA).

Example target distribution

As a simple example of a target distribution, we consider a

10-dimensional Gaussian target with heterogeneous scales such that the

standard deviation of the first coordinate is 0.01 and that of other

coordinates is 1. The rmcmc package expects the target

distribution to be specified by a function evaluating the logarithm of

the (potentially unnormalized) probability density at a point, and for

gradient-based methods such as the Barker proposal, additionally

requires specification of a function evaluating the gradient of this log

density function. The two functions should be wrapped in to a list under

the names log_density and gradient_log_density

respectively.

Creating proposal distribution

rmcmc provides implementations of several different

proposal distributions which can be used within a Metropolis–Hastings

based MCMC method:

-

barker_proposal(): The robust gradient-based Barker proposal proposed by Livingstone and Zanella (2022). -

langevin_proposal(): A gradient-based proposal based on a discretization of Langevin dynamics. -

hamiltonian_proposal(): A gradient-based proposal based on a discretization of Hamiltonian dynamics, simulated for a fixed number of integrator steps. With a single integrator step equivalent tolangevin_proposal. -

random_walk_proposal(): A Gaussian random-walk proposal.

Each function takes optional arguments which can be used to customize

the behaviour of the proposal such as the scalar scale of

the proposal, a vector or matrix defining the proposal

shape and routines to sample the auxiliary variables used

in the proposal.

Here we create an instance of the Barker proposal, using the default

values of all arguments. Rather than specifying fixed scale

and shape tuning parameters, in the next section we

illustrate how to set up adaptation of these parameters during a warm-up

stage to the chains.

proposal <- barker_proposal()Setting up adaptation of tuning parameters

rmcmc has support for adaptively tuning parameters of

the proposal distribution. This is mediated by ‘adapter’ objects which

define method for update the parameters of a proposal based on the chain

state and statistics recorded during a chain iteration. Below we

instantiate a list of adapters to (i) adapt the scalar scale of the

proposal distribution to coerce the average acceptance probability of

the chain transitions to a target value, and (ii) adapt the shape of the

proposal distribution with per-coordinate scaling factors based on

estimates on the coordinate-wise variances under the target

distribution.

adapters <- list(

scale_adapter(

algorithm = "stochastic_approximation",

initial_scale = dimension^(-1 / 6),

target_accept_prob = 0.574,

kappa = 0.6

),

shape_adapter(type = "variance", kappa = 0.6)

)Here we set the initial scale to

and the target acceptance probability to 0.574 following the guidelines

in Vogrinc, Livingstone, and Zanella (2023). This is equivalent to

the default behaviour when not specifying the initial_scale

and target_accept_prob arguments, in which case proposal

and dimension dependent values following the guidelines in Vogrinc, Livingstone, and Zanella (2023) will be used. Both

adapters have an optional kappa argument which can be used

to set the decay rate exponent for the adaptation learning rate. We set

this to 0.6, following the recommendation in Livingstone and Zanella (2022), in both cases.

The adapter updates will be applied only during an initial set of ‘warm-up’ chain iterations, with the proposal parameters remaining fixed to their final adapted values during a subsequent set of main chain iterations.

Sampling a chain

To sample a chain we first need to specify the initial chain state.

The rmcmc package encapsulates the chain state in a list

which tracks the current position of the chain, but also additional

quantities such as the auxiliary variables used to generate the proposed

perturbation to the state, and cached values of the log density and its

gradient once computed once at the current position to avoid

re-computation. The [chain_state()] function allows creation of a list

of the required format, with the first (and only required) argument

specifying the position. Alternatively we can directly pass a vector

specifying just the position component of the state to the

initial_state argument of [sample_chain()]. Here we

generate an initial state with position coordinates sampled from a

independent normal distributions with standard deviation 10, following

the example in Livingstone and Zanella (2022). For reproducibility

we also fix the random seed.

set.seed(791285301L)

initial_state <- chain_state(10 * rnorm(dimension))We now have everything needed to sample a Markov chain. To do this we

use the sample_chain function from rmcmc. This

requires us to specify the target distribution, proposal distribution,

initial chain state, number of adaptive warm-up iterations and

non-adaptive main chain iterations and list of adapters to use.

n_warm_up_iteration <- 10000

n_main_iteration <- 10000Here we sample a chain with

warm-up and

main chain iterations. We set trace_warm_up to

TRUE to record statistics during the adaptive warm-up chain

iterations.

barker_results <- sample_chain(

target_distribution = target_distribution,

proposal = proposal,

initial_state = initial_state,

n_warm_up_iteration = n_warm_up_iteration,

n_main_iteration = n_main_iteration,

adapters = adapters,

trace_warm_up = TRUE

)If the progress package is installed a progress bar will

show the chain progress during sampling. The return value of

sample_chains is a list containing fields for accessing the

final chain state (which can be used to start sampling a new chain), any

variables traced during the main chain iterations and any additional

statistics recorded during the main chain iterations. If the

trace_warm_up argument to sample_chains is set

to TRUE as above, then the list returned by

sample_chains will also contain entries

warm_up_traces and warm_up_statistics

corresponding to respectively the variable traces and additional

statistics recorded during the warm-up iterations.

One of the additional statistics recorded is the acceptance

probability for each chain iteration under the name

accept_prob. We can therefore compute the mean acceptance

probability of the main chain iterations as follows:

mean_accept_prob <- mean(barker_results$statistics[, "accept_prob"])

cat(sprintf("Average acceptance probability is %.2f", mean_accept_prob))

#> Average acceptance probability is 0.54This is close to the target acceptance rate of 0.574 indicating the scale adaptation worked as expected.

We can also inspect the shape parameter of the proposal to check the

variance based shape adaptation succeeded. The below snippet extracts

the (first few dimensions of the) adapted shape from the

proposal object and compares to the known true scales

(per-coordinate standard deviations) of the target distribution.

clipped_dimension <- min(5, dimension)

final_shape <- proposal$parameters()$shape

cat(

sprintf("Adapter scale est.: %s", toString(final_shape[1:clipped_dimension])),

sprintf("True target scales: %s", toString(scales[1:clipped_dimension])),

sep = "\n"

)

#> Adapter scale est.: 0.00922080029766185, 0.995077611400515, 0.975164196791254, 0.938742004951002, 0.959131700160353

#> True target scales: 0.01, 1, 1, 1, 1Again adaptation appears to have been successful with the adapted shape close to the true target scales.

Summarizing results using posterior package

The output from sample_chains can also be easily used

with external packages for analyzing MCMC outputs. For example the posterior

package provides implementations of various inference diagnostic and

functions for manipulating, subsetting and summarizing MCMC outputs.

library(posterior)

#> This is posterior version 1.6.1

#>

#> Attaching package: 'posterior'

#> The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':

#>

#> mad, sd, var

#> The following objects are masked from 'package:base':

#>

#> %in%, matchThe traces entry in the returned (list) output from

sample_chain is a matrix with row corresponding to the

chain iterations and (named) columns the traced variables. This matrix

can be directly coerced to the draws data format the

posterior package internally uses to represent chain

outputs, and so can be passed directly to the summarize_draws

function to output a tibble data frame containing a set

of summary statistics and diagnostic measures for each variable.

summarize_draws(barker_results$traces)

#> # A tibble: 11 × 10

#> variable mean median sd mad q5 q95 rhat ess_bulk

#> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 position1 1.63e-4 3.51e-4 0.0102 0.0104 -0.0166 0.0169 1.00 1197.

#> 2 position2 -3.07e-2 -9.21e-3 1.01 0.990 -1.72 1.62 1.00 1405.

#> 3 position3 2.22e-2 1.54e-2 1.01 1.01 -1.61 1.64 1.000 1191.

#> 4 position4 2.13e-2 1.25e-2 1.02 1.04 -1.68 1.68 1.000 1250.

#> 5 position5 1.78e-2 2.02e-2 0.993 1.01 -1.63 1.62 1.00 1370.

#> 6 position6 -2.23e-2 -3.13e-2 1.01 0.996 -1.67 1.65 1.00 1157.

#> 7 position7 2.99e-2 4.19e-3 1.00 1.01 -1.59 1.69 1.00 1456.

#> 8 position8 2.38e-2 -4.45e-3 1.02 1.01 -1.63 1.75 1.00 1503.

#> 9 position9 -3.08e-2 -3.23e-2 1.01 1.02 -1.67 1.62 1.00 1478.

#> 10 position10 2.73e-2 1.43e-2 1.01 1.02 -1.61 1.67 1.00 1482.

#> 11 target_log_de… -5.11e+0 -4.71e+0 2.34 2.17 -9.43 -2.00 1.00 1188.

#> # ℹ 1 more variable: ess_tail <dbl>We can also first explicit convert the traces matrix to

a posterior draws object using the

as_draws_matrix function. This can be passed to the

summary generic function to get an equivalent output

draws <- as_draws_matrix(barker_results$traces)

summary(draws)

#> # A tibble: 11 × 10

#> variable mean median sd mad q5 q95 rhat ess_bulk

#> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 position1 1.63e-4 3.51e-4 0.0102 0.0104 -0.0166 0.0169 1.00 1197.

#> 2 position2 -3.07e-2 -9.21e-3 1.01 0.990 -1.72 1.62 1.00 1405.

#> 3 position3 2.22e-2 1.54e-2 1.01 1.01 -1.61 1.64 1.000 1191.

#> 4 position4 2.13e-2 1.25e-2 1.02 1.04 -1.68 1.68 1.000 1250.

#> 5 position5 1.78e-2 2.02e-2 0.993 1.01 -1.63 1.62 1.00 1370.

#> 6 position6 -2.23e-2 -3.13e-2 1.01 0.996 -1.67 1.65 1.00 1157.

#> 7 position7 2.99e-2 4.19e-3 1.00 1.01 -1.59 1.69 1.00 1456.

#> 8 position8 2.38e-2 -4.45e-3 1.02 1.01 -1.63 1.75 1.00 1503.

#> 9 position9 -3.08e-2 -3.23e-2 1.01 1.02 -1.67 1.62 1.00 1478.

#> 10 position10 2.73e-2 1.43e-2 1.01 1.02 -1.61 1.67 1.00 1482.

#> 11 target_log_de… -5.11e+0 -4.71e+0 2.34 2.17 -9.43 -2.00 1.00 1188.

#> # ℹ 1 more variable: ess_tail <dbl>The draws object can also be manipulated and subsetted with various

functions provided by posterior. For example the extract_variable

function can be used to extract the draws for a specific named

variable. The output from this function can then be passed to the

various diagnostic functions, for example to compute the effective

sample size of the mean of the target_log_density variable

we could do the following

cat(

sprintf(

"Effective sample size of mean(target_log_density) is %.0f",

ess_mean(extract_variable(draws, "target_log_density"))

)

)

#> Effective sample size of mean(target_log_density) is 1206Sampling using a Langevin proposal

To sample a chain using a Langevin proposal, we can simply use

langevin_proposal in place of

baker_proposal.

Here we create a new set of adapters using the default

target_accept_prob argument to scale_adapter

which will set the target acceptance rate to the Langevin proposal

optimal value of 0.574 following the results in Roberts and Rosenthal (2001).

mala_results <- sample_chain(

target_distribution = target_distribution,

proposal = langevin_proposal(),

initial_state = initial_state,

n_warm_up_iteration = n_warm_up_iteration,

n_main_iteration = n_main_iteration,

adapters = list(

scale_adapter(algorithm = "stochastic_approximation", kappa = 0.6),

shape_adapter(type = "variance", kappa = 0.6)

),

trace_warm_up = TRUE

)We can again check the average acceptance rate of the main chain iterations is close to the specified target value:

cat(

sprintf(

"Average acceptance probability is %.2f",

mean(mala_results$statistics[, "accept_prob"])

)

)

#> Average acceptance probability is 0.61and use the ess_mean function from the

posterior package to compute the effective sample size of

the mean of the target_log_density variable

cat(

sprintf(

"Effective sample size of mean(target_log_density) is %.0f",

ess_mean(

extract_variable(

as_draws_matrix(mala_results$traces), "target_log_density"

)

)

)

)

#> Effective sample size of mean(target_log_density) is 2863Comparing adaptation using Barker and Langevin proposal

We can plot how the proposal shape and scale parameters varied during

the adaptive warm-up iterations, by accessing the statistics recorded in

the warm_up_statistics entry in the list returned by

sample_chain.

visualize_scale_adaptation <- function(warm_up_statistics, label) {

n_warm_up_iteration <- nrow(warm_up_statistics)

old_par <- par(mfrow = c(1, 2))

on.exit(par(old_par))

plot(

exp(warm_up_statistics[, "log_scale"]),

type = "l",

xlab = expression(paste("Chain iteration ", t)),

ylab = expression(paste("Scale ", sigma[t]))

)

plot(

cumsum(warm_up_statistics[, "accept_prob"]) / 1:n_warm_up_iteration,

type = "l",

xlab = expression(paste("Chain iteration ", t)),

ylab = expression(paste("Average acceptance rate ", alpha[t])),

ylim = c(0, 1)

)

mtext(

sprintf("Scale adaptation for %s", label),

side = 3, line = -2, outer = TRUE

)

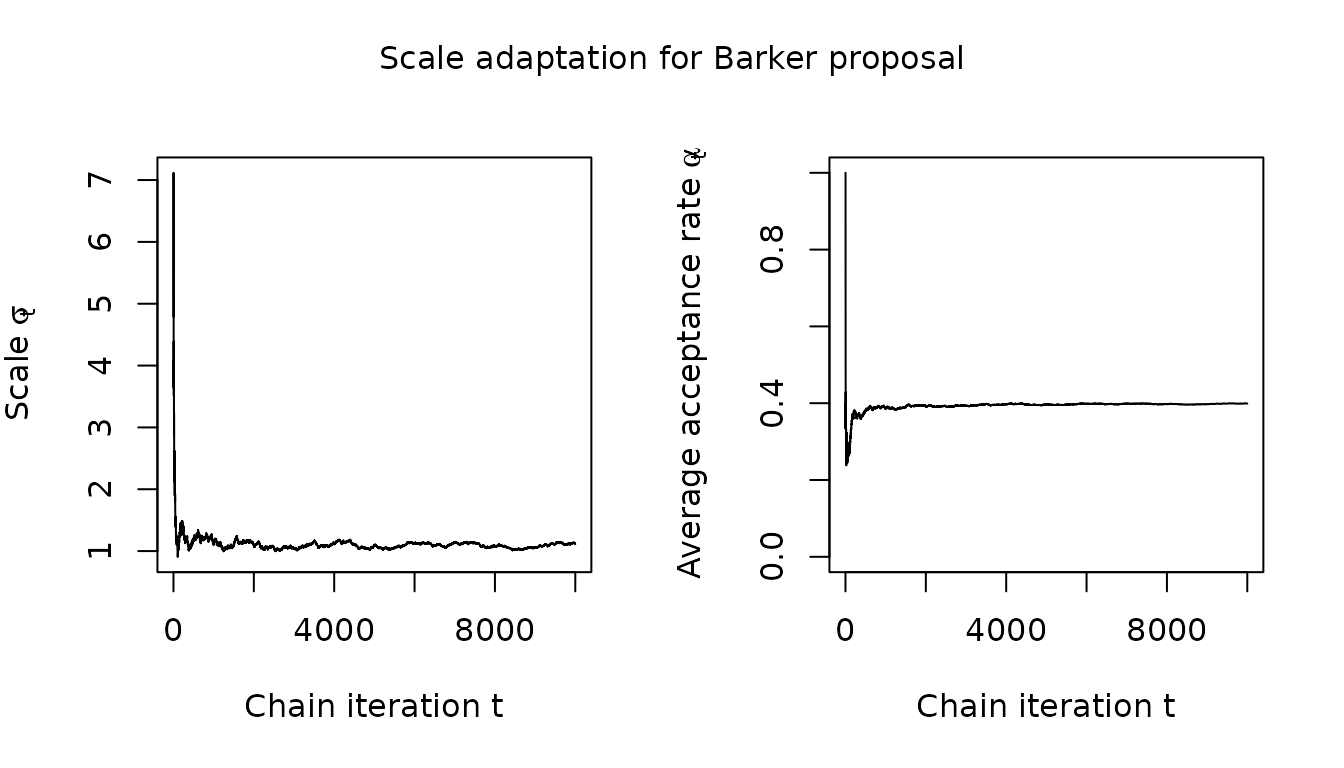

}First considering the scalar scale parameter , which is controlled to achieve a target average acceptance rate, we see that for Barker proposal the adaptation successfully coerces the average acceptance rate to be close to the 0.574 target value and that the scale parameter adaptation has largely stabilized within the first 1000 iterations.

visualize_scale_adaptation(barker_results$warm_up_statistics, "Barker proposal")

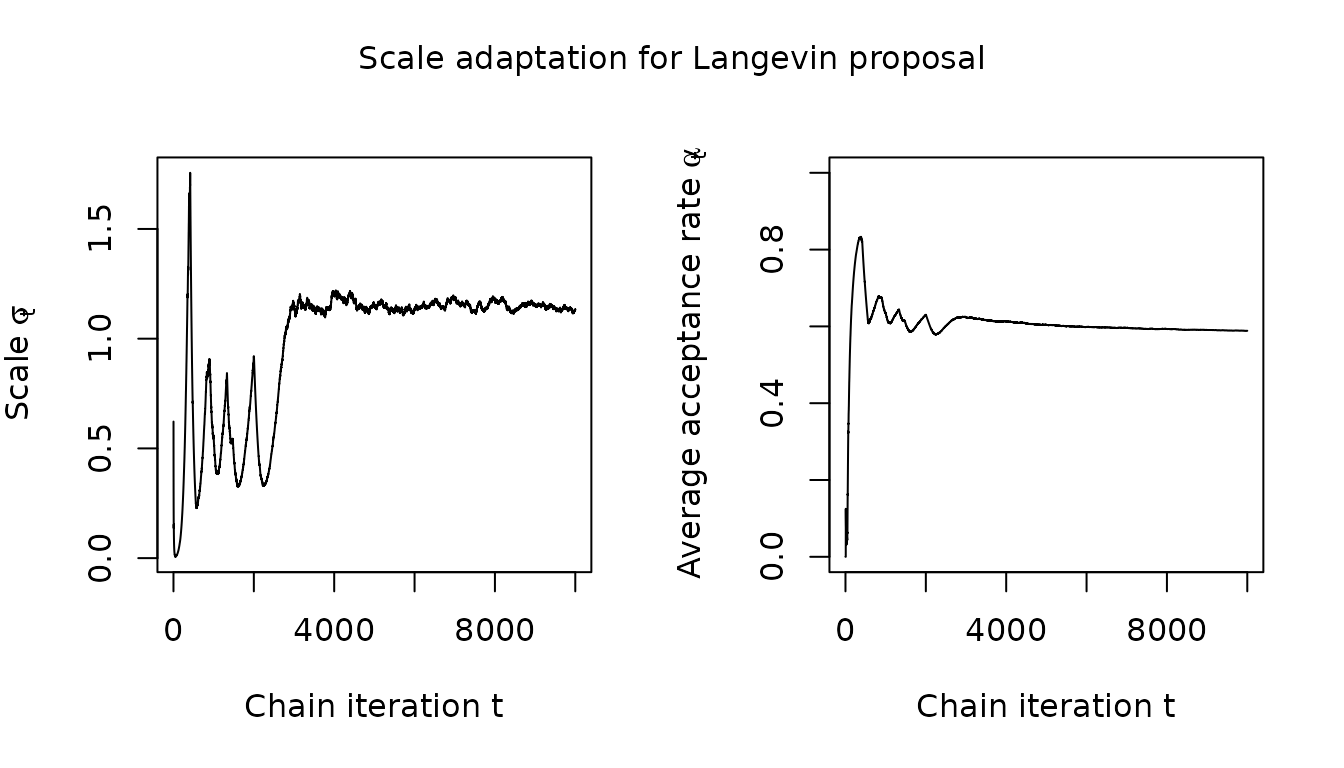

For the Langevin proposal on the other hand, while the acceptance rate does eventually converge to its target value of 0.574, the convergence is slower and there is more evidence of unstable oscillatory behaviour in the adapted scale.

visualize_scale_adaptation(mala_results$warm_up_statistics, "Langevin proposal")

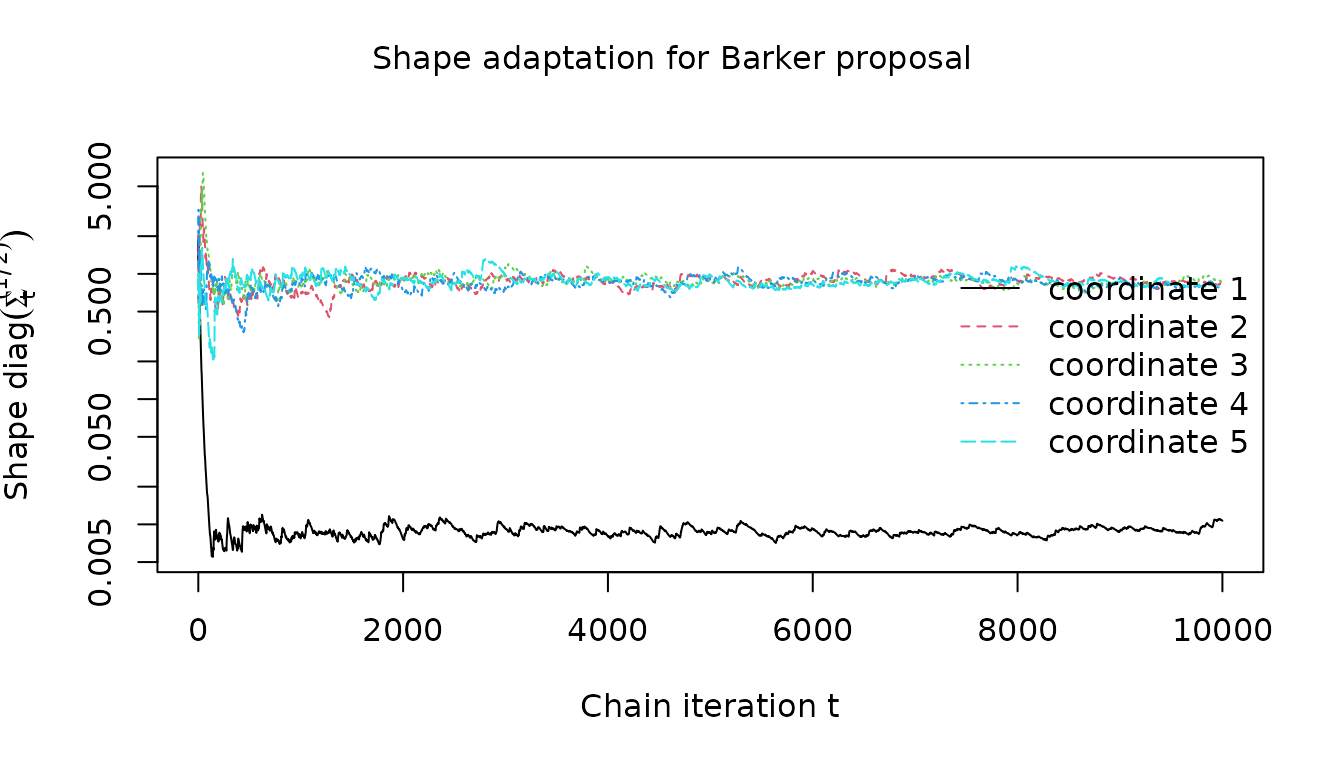

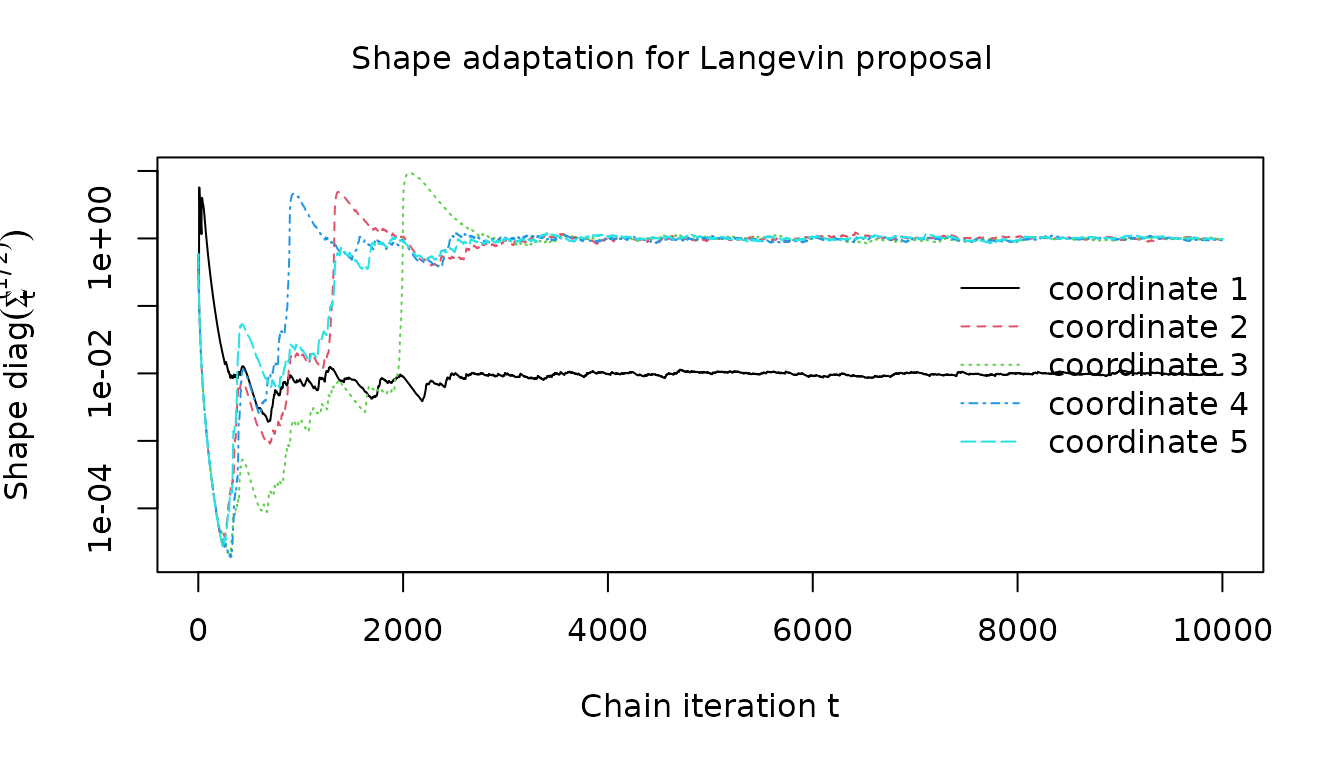

Now we consider the adaptation of the diagonal shape matrix , based on estimates of the per-coordinate variances.

visualize_shape_adaptation <- function(warm_up_statistics, dimensions, label) {

matplot(

sqrt(warm_up_statistics[, paste0("variance_estimate", dimensions)]),

type = "l",

xlab = expression(paste("Chain iteration ", t)),

ylab = expression(paste("Shape ", diag(Sigma[t]^(1 / 2)))),

log = "y"

)

legend(

"right",

paste0("coordinate ", dimensions),

lty = dimensions,

col = dimensions,

bty = "n"

)

mtext(

sprintf("Shape adaptation for %s", label),

side = 3, line = -2, outer = TRUE

)

}We see that the for the Barker proposal the adaptation quickly converges towards the known heterogeneous scales along the different coordinates.

visualize_shape_adaptation(

barker_results$warm_up_statistics, 1:clipped_dimension, "Barker proposal"

)

For the Langevin proposal, the shape adaptation is again slower.

visualize_shape_adaptation(

mala_results$warm_up_statistics, 1:clipped_dimension, "Langevin proposal"

)

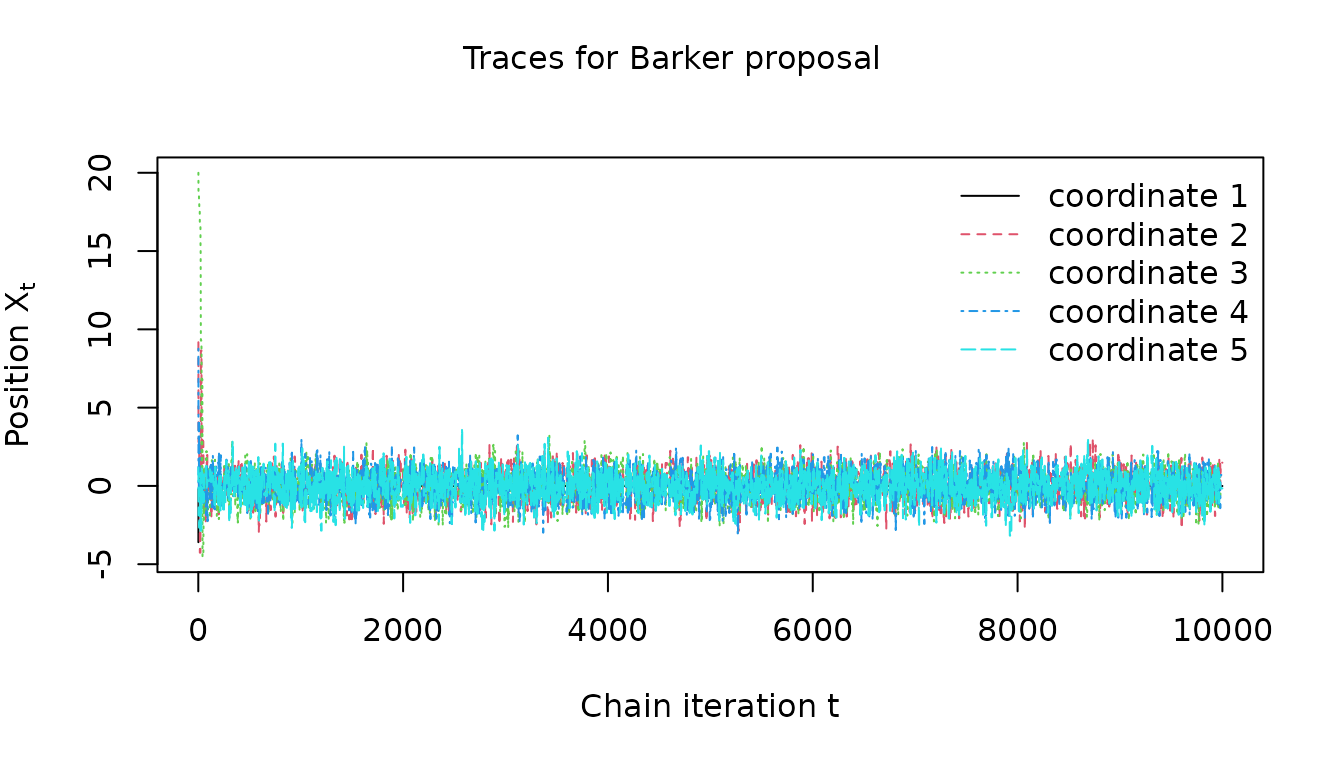

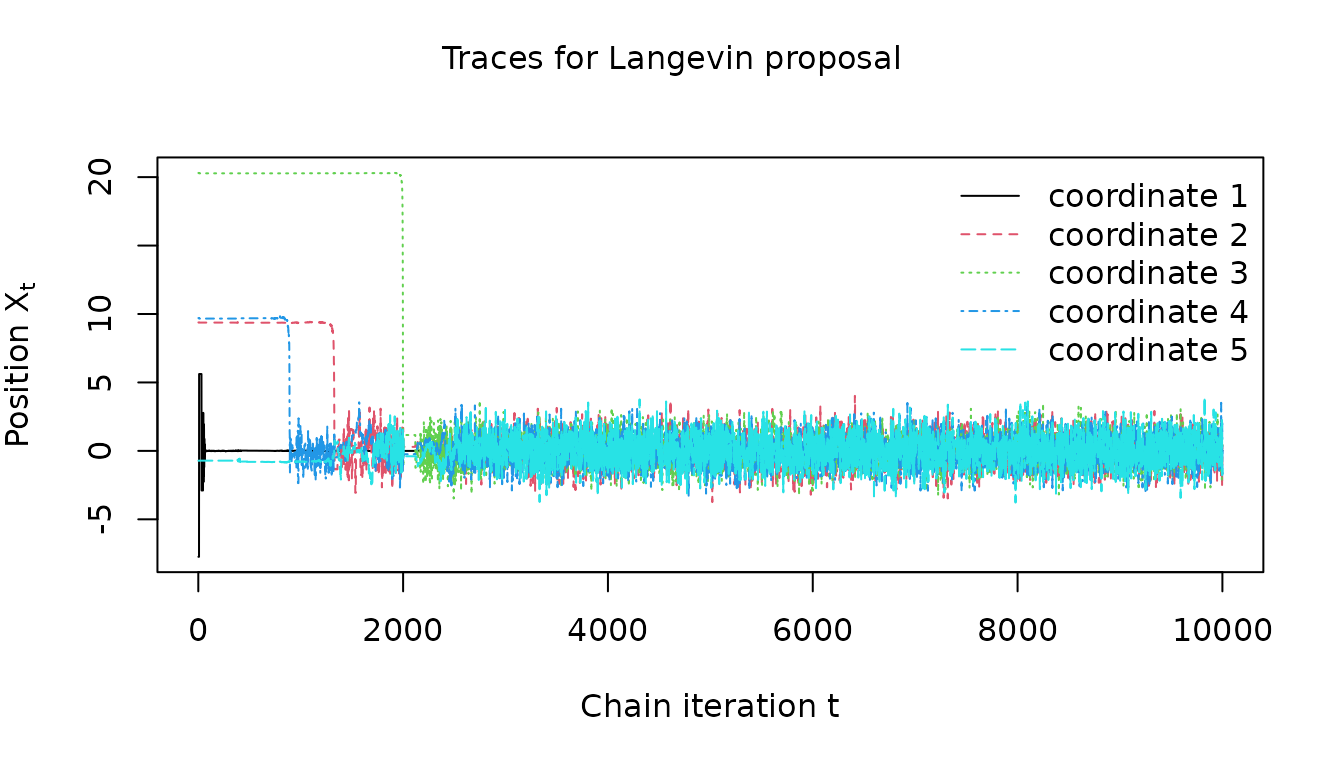

We can also visualize the chain position components during the

warm-up iterations using the warm_up_traces entry.

visualize_traces <- function(traces, dimensions, label) {

matplot(

traces[, paste0("position", dimensions)],

type = "l",

xlab = expression(paste("Chain iteration ", t)),

ylab = expression(paste("Position ", X[t])),

)

legend(

"topright",

paste0("coordinate ", dimensions),

lty = dimensions,

col = dimensions,

bty = "n"

)

mtext(sprintf("Traces for %s", label), side = 3, line = -2, outer = TRUE)

}For the Barker proposal we can see the chain quickly appears to converge to a stationary regime

visualize_traces(

barker_results$warm_up_traces, 1:clipped_dimension, "Barker proposal"

)

The Langevin proposal does also appear to converge to a stationary regime but again convergence is slower

visualize_traces(

mala_results$warm_up_traces, 1:clipped_dimension, "Langevin proposal"

)

Overall we see that while the Langevin proposal is able to achieve a higher sampling efficiency when tuned with appropriate parameters, its performance is more sensitive to the tuning parameter values resulting in less stable and robust adaptive tuning.